Bull in the Leather

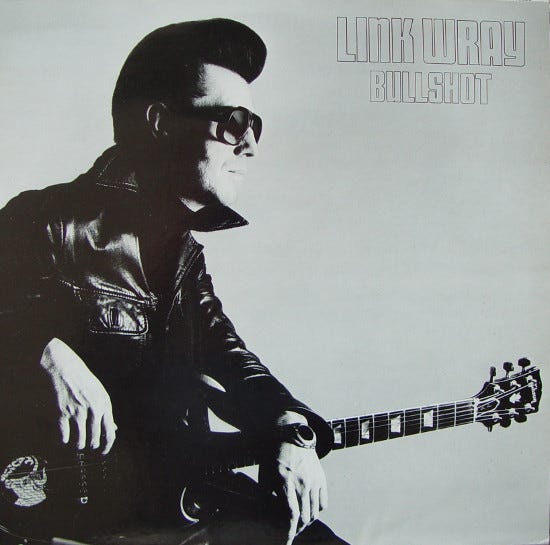

In honor of his birthday, a look back at 1979—the year Taurean mastermind Link Wray turned 50 and released 'Bullshot,' his 'middle finger to the machine.'

Hi, and welcome to the May edition of Switchblade.

I’ve been feeling under the weather the past couple weeks thanks to spring allergies, Pfizer vaccine #2 side effects (worth it!!!) and a bad…cold? I’d kind of forgotten about colds. Turns out they’re still terrible.

Book Updates

We’re now looking at a 2022 publish date for my Link Wray biography! There are a lot of loose ends are being tied up and final revisions being made. If you had told me when I signed my book deal in 2015—supposedly for quick-turn publication, lol—that in 2021 it would still not be out, I probably would have crumbled into a heap on the floor. Sometimes I still want to.

But part of writing about someone with a life, family, personality and career as big as Link’s is learning that it takes a whole lot more than a couple years of research and interviews to paint anywhere close to a complete picture. The extra time has meant finding additional, elusive sources, interviews, photos, obscure details and more thought put into how it all serves Link’s legacy. As a former magazine editor who’s used to being on super-strict monthly deadlines, it’s been extremely difficult for me to slow down and let this story marinate and occasionally change shape. But I’m so much happier with where it is now.

I finished my first draft of the manuscript in July 2016, two weeks after my son was born and a little over two years after my first research trip to Dunn, North Carolina. After hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of travel, interviews, organizing, writing, researching, fact checking, editing and rewriting later, in addition to working full time (and you know, parenting) we’re edging into final version territory with said child now about to enter kindergarten. Honestly, I don’t know what will freak me out more, the first day of school or the book finally coming out.

As always, this newsletter, plus Bazillion Points’ Instagram, is the best way to find out about pre-orders, pub date announcements, events and everything else book-related when the time comes.

Southside Pride

I’ve lived in South Minneapolis for nearly a decade, but somehow only recently discovered KRSM, a hyperlocal community radio station broadcasting out of the Phillips neighborhood. It immediately got a spot on my car radio presets, alongside KFAI and my alma mater Radio K, which I wrote about last month. To the KRSM DJ who segued smooth jazz right into Bel Biv Devoe’s “Poison” yesterday: We are kindred spirits.

Check out shows like Same As It Ever Was (new wave), Flavorsura (Latinx music) and Faderz and Buttonz (hip hop/R&B live mix) on KRSM, as well as a ton of BIPOC/LGBTQ-produced and -centered programming. They feature lots of Indigenous-focused content and there are shows in English, Spanish, Somali, Ojibwe, Hmong and Haitian Creole. Listen worldwide on their website or locally at 98.9 FM.

A Taurus Taking a Shot

May 2 is Link Wray’s birthday. If he were alive today, he’d be turning 92. So in honor of that, and his astrological sign (Taurus, the bull), I’m taking a look back at his 1979 album, Bullshot.

Bullshot came out the year that Link turned 50. Beyond being an important milestone birthday, Link’s 50th marked a huge shift personally and career-wise. In the years before Bullshot, he had been working with Robert Gordon on a well-received rockabilly collaboration. The two albums they did together gave Link a resurgence; introduced him to a whole new generation of musicians, fans and industry acolytes; and allowed him to tour Europe with Gordon. In 1977, Bruce Springsteen even gave them a song, “Fire,” that he’d originally intended for Elvis. It wasn’t a huge hit by any means, but it spent eight weeks on the Billboard charts—Link’s first charting song in two decades.

Sources I’ve interviewed for the book give slightly different explanations as to why exactly Link decided to leave this fruitful—and by all accounts, mutually respectful and fond—partnership behind to re-embark on a solo career. Many, including Gordon himself, say that Link simply played too loud for anyone to be in a band with him. (This is actually a very common refrain from people in all stages of Link’s career.) So in June 1978, they parted ways musically but remained close friends.

Link had already lost his mother, Lillian, in 1975. A month after Link left Gordon, Link’s father passed away; his older brother Ray (né Vernon) died in March 1979. Link had been especially close to Lillian. And while his relationship with his older brother had been contentious and fraught with financial and personal misdeeds, they shared an unbreakable (for better or worse) bond. They stuck together, sometimes even living together, ever since their family-band days playing Western Swing at dude ranches in post-World War II Virginia. Ray’s death by suicide had to have crushed Link, although he typically projected an air of pragmatism about it.

Ray had been in the studio with Link in some capacity for most of his career, and Bullshot was Link’s first release since his older brother’s death. Aided by Gordon/Wray producer Richard Gottehrer, Link assembled the rest of Gordon’s band: bassist Rob Stoner, drummers Howie Wyeth and Anton Fig, and rhythm guitarist Billy Cross. The result was one of Link’s slickest albums—an indication of the direction he might have headed if he’d listened to his record labels’ advice or ever stuck with a producer that wasn’t his brother. Even with Ray gone, there was a familial element, with Link’s beloved younger brother Doug and 9-year-old daughter Rhonda contributing backing vocals.

Within a few years of Bullshot’s release, Doug would die young of a heart attack and Link would be the only remaining member of his immediate family. He would divorce his third wife (and Rhonda’s mother), Sharon to marry Olive, a much younger woman. He’d soon permanently relocate to Olive’s home country of Denmark, leaving behind eight children and three ex-wives in the United States, returning only occasionally to tour. Almost everyone I’ve interviewed who knew Link at this time says that he was a different person after Doug’s death in 1984, and I suspect that along with the other impetuses—other family members’ deaths, leaving Gordon, turning 50 and divorcing Sharon—Bullshot was an important marker of, and contributor to, that transformation.

Among fans, feelings are mixed about Bullshot. I happen to love it. It’s a no-frills power-rock album that starts and finishes strong. You can catch glimpses of Link’s late-career pop prowess in songs like “Good Good Lovin’,” “Just That Kind” and “Wild Party.” His supercharged cover of the 1956 Little Wille John song “Fever” is distorted darkwave disco, while his covers of Elvis’ “Don’t” and Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” are fan favorites.

There’s also the classic Link move: revisiting his old hits, including an updated version of “Raw-Hide” and “Snag,” a twist on his 1958 song “The Swag,” which had been used in 1972 John Waters film Pink Flamingos.

And of course we can’t forget the brooding “Switchblade,” which is the namesake of this very newsletter.

One of the sources I interviewed for the book was Bullshot bassist Rob Stoner. Stoner, né Robert Rothstein, already had a successful solo country career when he met Link, in addition to extensive experience in the studio and touring with people like Chuck Berry, Pete Seeger, Roy Orbison, Joan Baez, and Don McLean (including playing on the American Pie record). He also was a member of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. He had this to say about the album:

This could be my very favorite thing I ever played on—and I played on American Pie, Bob Dylan records, every kind of heavy metal record, you name it.

Stoner says the name was inspired both by Link’s astrological sign (the infamously stubborn Taurus) as well as the fact that he was leaving Robert Gordon behind to go out on his own again.

It was a pun on ‘bullshit.’ It was Link’s shot, putting out a solo album [after leaving Robert Gordon’s band]. So it’s a Taurus taking a shot.

To me, Bullshot—and all of 1979—is Link in limbo, stuck in time. He’s already lost his parents and his sibling/lifelong musical partner, and his third marriage is on the verge of implosion. He’s moved on with Olive, but doesn’t want to let Sharon go completely. He’s creating on-trend rock songs, but putting them right alongside rehashed old hits. He’s making a fresh start, but still hires Robert Gordon’s producer and band.

A recurring theme in Link’s life was his stubborn refusal to let go of his past to make way for his future, and Bullshot is the apex of that. I looked up the word “Taurean” to make sure it was spelled right and just had to laugh at the example sentences. Lo and behold, Link is the literal dictionary definition of a Taurean. He famously never forgot or forgave—and he certainly let his Taurean stubbornness guide him.

Despite his late-‘70s resurgence and the respected producer and musicians attached to the project (as well as a healthy budget), Bullshot fizzled out and Link moved on. Within a year he would marry Olive; within five, he would be in Denmark.

In the years immediately following Bullshot, and especially after Doug’s death, Link let go of that attachment to the past, although he never stopped rehashing his old songs. He left behind his eight children to move to a new country with hardly any contact until his death 20-odd years later. At the urging of Olive, he severed ties with old friends, family members, music industry associates and bandmates who loved and supported him. When he did tour the States, he refused to play the cities like D.C. and Portsmouth where he’d started his career, nor would he pick up the phone to call his kids. He chose to overcorrect in an equally unhealthy way, forgoing the past altogether in favor of his new life.

According to those who spoke with him about it decades later, he looked back at Bullshot with mixed emotions. Justin McDonald, a member of Seattle band Jet City Fix, opened for Link and played bass in his band on a 2003 tour. He remembers Link telling him that Bullshot was a “middle finger to the machine.”

He wanted to call the record Bullshit—but obviously he couldn’t do that in 1979—because he thought that the industry was bullshit and they were [just] getting all this money.

Drummer Jade Dylan, who toured with Link on and off from 1999 to 2003, says that Link thought Bullshot was a regrettable attempt to break into mainstream rock. Here are some of Dylan’s thoughts on it:

Bullshot, that represents to me the good intentions of established people. It’s a slick album; it sounds good. But to me, it’s too slick. It’s just too clean [and doesn’t have] the heart of what was going on. No disparaging Anton Fig—he’s a fucking legend in his own right, I’ll never do that. But they just didn’t get it right, I don’t think.

We can’t know Link’s thoughts, and honestly Link probably couldn’t even pinpoint how he felt about it on any given day. But no matter how you feel about the music, Bullshot is an important snapshot of a huge turning point in Link’s life. And a hell of a way to ring in your 50th birthday.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll talk to you next month.